Dance-Opera: The Governor’s Death

Excerpts from the notes written in 1997 by János Kodolányi dealing with the circumstances and events about the performance of a “total theater”

János Kodolányi: Notes to The Governor’s Death

My text of the poem cannot be considered as a libretto. This poetic cycle is filled with the expectations perceivable in 1989, this parting and glorious historic moment, together with the live experience of dictatorship. The history of the birth of this work of total theater might bring the reader closer to The Governor’s Death.

The idea of The Governor’s Death started to grow in the imagination of my friend, the composer György Szabados, from 1986 onwards. Szabados was aware of certain forgotten mythic elements emerging from time to time among the fragments of the Hungarian folk play. He recognized in them a relationship with some motives of Japanese and Chinese Theaters. This gave him the impulse to create such a modern play, in which the vision and style of the kabuki theatre shine through our problems, our sensibilities.

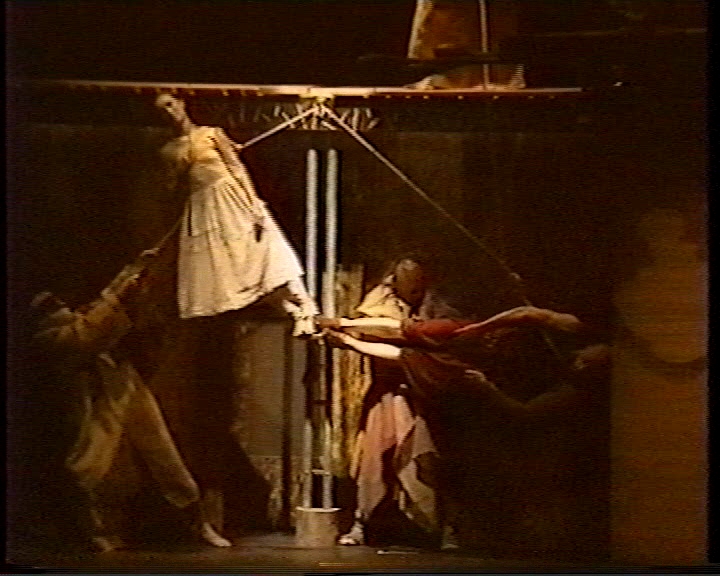

Szabados was thinking of a play, which would give the same importance to music, recitation, and motion, and which is completely different from all that we know as opera or ballet – more stylized in a certain sense, more rough, in a certain regard – not anecdotic, and not naturalistic.

During those days Szabados got to know and became friends with József Nagy, aka Josef Nagj, during his visit in Bácska (today Serbia). Nagy was the choreographer-dancer of the JEL Theatre and was preparing for his first big production, titled Peking Duck, which made him one of the leading personalities of the modern dance theatre in Paris. Witnessing the workshop of Nadj and the Peking Duck’s performance, Szabados realized that all that he was playfully shaping in his imagination could be executed, because there was a director as well as a theatre eager to produce something similar.

I joined the process of creation of this play during the spring 1989. Szabados had already mentioned to me in 1988 about the cooperation, and that he was looking for a librettist – but at this time I didn’t make use of the opportunity. I had never written anything for the stage and my understanding about drama went in a different direction. By the time I joined, the main lines of the action and the tone set limits to the space of movement. From then on, the three components, dance, music, and poetry, followed different paths, but they had been created simultaneously, influencing each other. Nadj supplied the videos of the dance rehearsals in Paris. We discussed them with him, with the musicians, and with Szabados and I. I supplied the new poems to Szabados and Nadj, which became the subject of our very objective discussions in Nagymaros. Szabados made comments on our work, bearing in mind the music’s dynamics and the drama’s swell.

There was no complete drama that needed music and choreography. There was no ready story asking for a libretto. We together created something step by step, with jumps and detours in the free space of the huge, imaginary form; this was extraordinarily difficult, but liberating.

The three of us each contributed a different dimension to The Governor’s Death. Szabados accepted, like me, that the motion starts sooner, earlier, from a deeper dimension, then music and poesy follows. Nadj imagined the story, which the dance theatre could express in the language of motion, and this required a new music which is alert to the dialect of the stage, while keeping its, (the music’s) autonomy. Later, in the phase of maturing, the dance had to adjust itself to the direction of the unfolding music, which already included my text for recitation. The text itself however, had an impact on the tones, forms, and extent of the music.

Through my text, the narrator himself – Tamás Kobzos Kiss in this case – entered the drama too, since the view expressed in the poems is shifting in The Governor’s Death. At the beginning, the view identifies itself with the lies surrounding the tyrant, and this hypocrisy can be revealed only by the distortions and warps of the tone. This is the irony in the text, which is hidden from the “user” of this language. The text’s deranged metaphors and slips of tongues make a mockery of the self-glorification of any dictatorship, gladly perceivable for the sensitive ear.

In the course of the play the Narrator is confronted with the reality and experiences of an almost as powerful enlightenment as the Fool did. This bestows upon him the awareness to speak the final words of the play and evoke even a kind of vision about the future, which is a counterpart to the light shining through the ‘House-saint’ at the end of the play.

Finally, a few words about the silence, about the theatre of silence.

In 1989 we had the impression that the time of the overacted pantomime of lies and of the extreme emotions has come. The Governor pours a sauce of deceiving smugness upon the common understanding, knocked together by force; in this world governs thus the “double speech”, the trapping and tripping up of others, and the secret play in every human relationship. Only two; outside tragicomic, inside however, even more powerful human voices scream through the choir of hypocrisy. One is the voice of love of the Fool (and court poet) to the House-saint, the other is her compassion to the Governor. It turns out that when somebody in this world wants to be good or “different” without acting – when somebody wants to be “beautiful and free and soft” by using his own miserable means – sooner or later he will induce rebellion. The power will finally waver from inside, at the moment when it tries to humiliate this silent opposition with brutal means.

Were we mistaken? In November 1989, the day when the group of Nadj and MAKUZ – the Hungarian Royal Court Orchestra, under the musical direction of Szabados – performed for the first time the dance opera in Brest (France), the Berlin Wall came down.

Translation by Marianne Tharan (October 2017)