BIOGRAPHY:

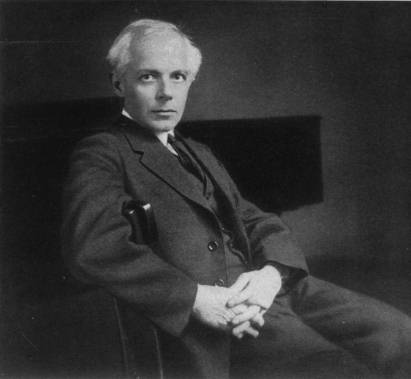

Béla Bartók

was a Hungarian composer and pianist.

(March 25, 1881 – September 26, 1945)

He is considered one of the most important composers of the 20th century; he and Liszt are regarded as Hungary’s greatest composers (Gillies 2001). Through his collection and analytical study of folk music, he was one of the founders of comparative musicology, which later became ethnomusicology.

Involved in György Szabados "Body of Work":

Only from Pure Mountain Springs” Folk Tradition in Hungarian Jazz (an essay by Zoltán Szerdahelyi) (excerpt)

The greatest Hungarian composer, Béla Bartók (1881-1945), found the symbol of man sated with civilisation and yearning for natural purity in the Romanian folk ballad about the nine hunters turned into stags. The story can be seen as a spiritual-magical aid offered to man believing in his own truthfulness and moral strength to extricate himself and face his own freedom. This message has become a universal symbol and its source is present in the myths and folk poetry of virtually all peoples. The legend of the nine miraculous stags is one of the origin myths of the Romanians. However, its ties to the Hungarian legend of Hunor and Magor are obvious.

The message of Bartók’s musical piece Cantata Profana – The Nine Miraculous Stags is important for ethno jazz musicians:… Their slender bodies

Ne’er in clothes can wander

Only wear the wind and sun,

Their dainty legs

Can never stand the hearthstone,

Only tread the leafy mold;

Their mouths no longer

Drink from crystal glasses,

Only from pure mountain springs.‘Only from a pure source’ is a wish omnipresent in the work of the father and unofficial king of free jazz based on Hungarian folk music – GYÖRGY SZABADOS“

LINER NOTES to CD: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() (1998: Az idő múlása / Time Flies) (excerpt):

(1998: Az idő múlása / Time Flies) (excerpt):

In successive years before the Hitler war, composer Béla Bartók toured England and Scotland, travelling alone from station to station and from concert hall to concert hall. Those who heard him responded to his brilliant technique, to his brilliant synthesis of tradition and modernity, and to a touch of sadness in his person.

Those lucky enough to witness him practise, unobserved by a formal audience, noted that when he sat down at the keyboard of an unknown piano, he would spend some minutes playing rippling improvisations on half-remembered and perhaps imaginary folk-tunes. It was the music of a man far from home and familiar scenes, a man gripped by nostalgia in its proper sense.

Something of that quality shines through in the work of György Szabados, though the sadness of the blues has as large a part in his musical background as the grief-songs of the Magyar kingdom had in Bartók’s. It is clear that “Golden Age” and “Memory”,which precedes it, grow from some nostalgic spring deep within. The technique is strikingly similar to what survives of Bartók’s on record-the same light, unemphatic touch that makes its case by persuasion and reason rather than histrionics, the same delicately pedalled sustains and damped notes, the same insistence on the continuity of self and art.

LINER NOTES to CD: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() (2003: Triotone [Braxton–Szabados–Tarasov Trio]) (excerpt):

(2003: Triotone [Braxton–Szabados–Tarasov Trio]) (excerpt):

A Digression on the Improvisatory Spirit of Hungarian Music

As improvisation continues to assert its claim as the essential musical practice, it’s important to note the particular contours of its demise in European music. If he was not the last great improviser in nineteenth-century music, Franz Liszt was very perhaps the last to be celebrated, playing concerts at age 12 that included “extemporized” music in which he would invite audience members to suggest themes (Michael Furstner, “On Improvisation”). As well as being a virtuoso solo improviser, Liszt was aware of a tradition of collective improvisation in the folk music practice of rural Hungary. In the Hungarian Rhapsodies he began to mine idiomatic music in the interests of cultural nationalism (though they were evidently based on urban popular songs rather than authentic rural folk materials, but then Brahms’ Hungarian Dances were inspired by working as accompanist to a Hungarian violinist in Germany).

Liszt’s virtuosity and his later use of dissonance and bi-tonality (a kind of proto-modernism) lead naturally to the brilliant percussive freedom of early modernist piano music, a style developed largely in Eastern Europe by Bartók and Prokofiev. The expressionist, gestural quality of much of this music feels improvised, and has had significant impact on free jazz piano technique (one might also note the influence of Scriabin on Bill Evans).

The tonal materials of much Eastern European folk music have always been far enough away from triadic harmony and tempered scales to alter substantially the very Western forms that would integrate them (hence, the special appeal of the Bulgarian Women’s Choir for its command of microtonal singing). Eastern European music is modal music, with intimate connections to the Orient and the Near-East. In Hungary the bond between these traditions and modernist composition are particularly strong. It was modernist composers — Béla Bartók and Zoltan Kodely — who carried out the major field work on the country’s rural musical traditions.

Bartók has long been a favourite of jazz musicians, for the freedom and complexity of his harmonic language and that so much of his music feels improvised and invites improvisation. In 1938 Benny Goodman commissioned the trio piece Contrasts and recorded it with the composer at the piano. Lee Konitz’s recently reissued Piecemeal (Milestone/OJC) includes three arrangements of Bartók’s Mikrokosmos piano pieces and John Abercrombie’s recent Class Trip (ECM) includes his “Soldier’s Song.”

So if it was jazz that would introduce Szabados to improvisational practice, once the step had been taken there was another wellspring, geographically immediate, to draw on. The rhythms that drive his music, the characteristic intervals and scales, are in the musics of Eastern Europe, and his piano playing owes more to Bartók (with a nod to Thelonious Monk) than to the free jazz streams of either Cecil Taylor (who shares some of the same pianistic roots) or Paul Bley.

Corrections and additions are welcome – please contact webmaster: info@györgy-szabados.com