– COMPOSITIONS –

A kormányzó halála

A kormányzó halála

The Governor’s Death

The Governor’s Death

Der Tod des Gouverneurs

Der Tod des Gouverneurs

Year of writing:

Dance Opera – Musical Drama: 1989 (rising from a first idea in the year 1986)

Idea & Music: György Szabados

Text and Poems: Gyula Kodolányi – poems in Hungarian

Choreography and stage setting: Josef Nadj

First known performance:

Recording Date: 1989, 9 November

Recorded at: unknown location, Brest (F)

Year of publishing:

1990, VHS release

Music Publisher:

A kormányzó halála

Részletek Kodolányi Gyula 1997-ben irt jegyzeteiből egy totális színház történéseiről:

JEGYZETEK „A KORMÁNYZÓ HALÁLÁ”HOZ

Az én versszövegem nem librettó. Ez a ciklus viseli magán 1989, e távolodó, fényes történelmi

pillanat várakozásait, a diktatúra még eleven élményével együtt. A totális színházi mű keletkezésének története viheti talán közelebb az olvasót A kormányzó halálához.

A kormányzó halálának ötlete valamikor 1986-ban kezdett növekedni Szabados György zeneszerző barátom képzeletében. Szabados felfigyelt a magyar népi színjátszás emlékei közt töredékesen felbukkanó, elfeledett mitikus elemekre, s ezekben a japán és kínai színház motívumainak rokonságára ismert. Ezek indították olyan korszerű játék létrehozása felé, amelyben a kabuki színház szemlélete és stílusa szűrődik át a mi problémáinkon, a mi érzékenységünkön.

Olyan játékról gondolkodott Szabados, amelyben zenének, recitálásnak és mozgásnak egyforma szerep jut – s ami egészen más, mint amit mi opera vagy balett néven ismerünk. Bizonyos tekintetben stilizáltabb, bizonyos tekintetben sokkal nyersebb. Nem anekdotikus és nem naturalista.

Szabados ekkoriban, egyik bácskai látogatásán barátkozott össze Nagy Józseffel, alias Josef Nadjgyal, a Theatre Jel koreográfus-táncosával, aki éppen első nagy produkciójára készült, a „Pekingi kacsá”-ra, amellyel a párizsi modem táncszínház egyik vezető egyéniségévé lépett elő. Szabados a „Pekingi kacsa” és Nadj műhelymunkája láttán felismerte, hogy amit ő szinte csak játékként szövögetett a képzeletében, létrejöhet, mert van rendező, van színház, amely valami hasonlót akar megteremteni.

A játék létrehozásának folyamatába én 1989 tavaszán kapcsolódtam be. Szabados már 1988-ban említette nekem az induló együttműködést, s hogy szövegírót keres, de akkor még nem kaptam az alkalmon. Színpadi művet sosem írtam, és drámaelképzeléseim más irányban keresgéltek. Belépésem idejére a cselekmény fő vonalai és a mű hangneme már megteremtették a mozgásteret. Ettől fogva a három szál, a tánc, a zene és a vers külön utakon, de egyidejűleg, egymásra hatva jött létre. Nadj hozta a friss videofelvételeket a párizsi mozgáspróbákról. Ezeket újra és újra megbeszéltük, vele is, a zenészekkel is, és ketten Szabadossal. Én vittem az új verseket Szabadosnak és Nadjnak végtelen, de nagyon tárgyszerű nagymarosi diskurzusainkra. Szabados mindkettőnk munkáját folytonosan kommentálta, a zene dinamikáját és a dráma hullámzását tartva szem előtt.

Nem volt itt kész dráma, amelyet meg kellett zenésíteni, majd koreografálni. Nem volt kész történet, amely librettót kívánt. Együtt hoztunk létre valamit, lépésről lépésre, ugrásokkal és kitérőkkel, a nagy, elképzelt forma szabad terében: ez rendkívül nehéz volt, de felszabadító is.

Hárman más-más dimenziót adtunk A kormányzó halálához. Szabados elfogadta, amint én is, hogy a mozgás előbb, korábban, mélyebbről indul el, mint a zene és a költészet. Nadj képzelte el azt a történetet, amelyet a táncszínpad el tud mondani a mozgás nyelvén, s ehhez új zene kellett, amely minden öntörvényűsége mellett erre a színpadi dialektusra figyel. S majd a kiérlelés stádiumában ismét a táncnak kellett igazodnia a kibontakozó zene útmutatásaihoz, amely már az én, recitálandó szövegemet is magába foglalta. A csupasz szöveg befolyásolta viszont a zene tónusait, formáit, terjedelmét.

Szövegem révén a narrátor – az előadáson Kobzos Kiss Tamás – maga is belépett a drámába, hiszen a versekben kifejeződő nézőpont maga is mozog A kormányzó halálában. Kezdetben teljesen azonosul a zsarnokot körülbélelő hazugságokkal, és ezt a képmutatást a hangnem csorbulásai, zökkenői leplezhetik csak le, ez a szövegirónia, amely a használó előtt rejtve marad, s amelynek képzavarai, elszólásai oly vigasztalón nevetségessé teszik az érzékeny hallás számára a mindenkori diktatúrák öntömjénezését.

A játék során a narrátor szembesül a valósággal, és csaknem olyan erejű megvilágosodáson megy át, mint a bolond. Ezért lehet ő az, aki elmondja a történet végszavait, és valamiféle jövősejtelmet is megidéz, amely a háziszentet a játék végén átragyogó fényre rímel.

Szólnunk kell végül a csendről, a csend színházáról.

Úgy éreztük 1989-ben, hogy most a hazudozás túljátszott pantomimjának és a szélsőséges, ellentétükbe forduló indulatoknak jött el az ideje. A kormányzó hazug önelégültség mázával önti le az erőszakkal összekalapált társadalmi közmegegyezést: ebben a világban tehát a kettős nyelv, a betartás és a főalatti játék uralkodik minden emberi kapcsolatban. Csak két, külsőleg esendően tragikomikus, belsőleg annál erősebb emberi hang szólal fel a képmutatás kórusából: a bolond (és udvari költő) szerelme a háziszent vagy „szentecske” iránt, s az utóbbi részvéte a kormányzó iránt. Kiderül, hogy aki tétlenül jó avagy „más” az ilyen világban – aki „szép és szabad és szelíd” akar lenni a maga szánnivaló eszközeivel -, az lázadásra indító botránykővé válik előbb-utóbb. A hatalom éppen akkor rendül meg végleg belül, amikor ezt a csendes ellenállást próbálja brutálisan megalázni.

Tévedtünk-e? 1989 novemberében azon a napon, amikor a franciaországi Brestben először mutatta be a játékot Nadj társulata és a Makuz – Magyar Királyi Udvari Zenekar – Szabados vezetésével, omlott le a berlini fal.

Dance-Opera: The Governor’s Death

Excerpts from the notes written in 1997 by Gyula Kodolányi dealing with the circumstances and events about the performance of a “total theater”

Gyula Kodolányi: Notes to The Governor’s Death

My text of the poem cannot be considered as a libretto. This poetic cycle is filled with the expectations perceivable in 1989, this parting and glorious historic moment, together with the live experience of dictatorship. The history of the birth of this work of total theater might bring the reader closer to The Governor’s Death.

The idea of The Governor’s Death started to grow in the imagination of my friend, the composer György Szabados, from 1986 onwards. Szabados was aware of certain forgotten mythic elements emerging from time to time among the fragments of the Hungarian folk play. He recognized in them a relationship with some motives of Japanese and Chinese Theaters. This gave him the impulse to create such a modern play, in which the vision and style of the kabuki theatre shine through our problems, our sensibilities.

Szabados was thinking of a play, which would give the same importance to music, recitation, and motion, and which is completely different from all that we know as opera or ballet – more stylized in a certain sense, more rough, in a certain regard – not anecdotic, and not naturalistic.

During those days Szabados got to know and became friends with József Nagy, aka Josef Nagj, during his visit in Bácska (today Serbia). Nagy was the choreographer-dancer of the JEL Theatre and was preparing for his first big production, titled Peking Duck, which made him one of the leading personalities of the modern dance theatre in Paris. Witnessing the workshop of Nadj and the Peking Duck’s performance, Szabados realized that all that he was playfully shaping in his imagination could be executed, because there was a director as well as a theatre eager to produce something similar.

I joined the process of creation of this play during the spring 1989. Szabados had already mentioned to me in 1988 about the cooperation, and that he was looking for a librettist – but at this time I didn’t make use of the opportunity. I had never written anything for the stage and my understanding about drama went in a different direction. By the time I joined, the main lines of the action and the tone set limits to the space of movement. From then on, the three components, dance, music, and poetry, followed different paths, but they had been created simultaneously, influencing each other. Nadj supplied the videos of the dance rehearsals in Paris. We discussed them with him, with the musicians, and with Szabados and I. I supplied the new poems to Szabados and Nadj, which became the subject of our very objective discussions in Nagymaros. Szabados made comments on our work, bearing in mind the music’s dynamics and the drama’s swell.

There was no complete drama that needed music and choreography. There was no ready story asking for a libretto. We together created something step by step, with jumps and detours in the free space of the huge, imaginary form; this was extraordinarily difficult, but liberating.

The three of us each contributed a different dimension to The Governor’s Death. Szabados accepted, like me, that the motion starts sooner, earlier, from a deeper dimension, then music and poesy follows. Nadj imagined the story, which the dance theatre could express in the language of motion, and this required a new music which is alert to the dialect of the stage, while keeping its, (the music’s) autonomy. Later, in the phase of maturing, the dance had to adjust itself to the direction of the unfolding music, which already included my text for recitation. The text itself however, had an impact on the tones, forms, and extent of the music.

Through my text, the narrator himself – Tamás Kobzos Kiss in this case – entered the drama too, since the view expressed in the poems is shifting in The Governor’s Death. At the beginning, the view identifies itself with the lies surrounding the tyrant, and this hypocrisy can be revealed only by the distortions and warps of the tone. This is the irony in the text, which is hidden from the “user” of this language. The text’s deranged metaphors and slips of tongues make a mockery of the self-glorification of any dictatorship, gladly perceivable for the sensitive ear.

In the course of the play the Narrator is confronted with the reality and experiences of an almost as powerful enlightenment as the Fool did. This bestows upon him the awareness to speak the final words of the play and evoke even a kind of vision about the future, which is a counterpart to the light shining through the ‘House-saint’ at the end of the play.

Finally, a few words about the silence, about the theatre of silence.

In 1989 we had the impression that the time of the overacted pantomime of lies and of the extreme emotions has come. The Governor pours a sauce of deceiving smugness upon the common understanding, knocked together by force; in this world governs thus the “double speech”, the trapping and tripping up of others, and the secret play in every human relationship. Only two; outside tragicomic, inside however, even more powerful human voices scream through the choir of hypocrisy. One is the voice of love of the Fool (and court poet) to the House-saint, the other is her compassion to the Governor. It turns out that when somebody in this world wants to be good or “different” without acting – when somebody wants to be “beautiful and free and soft” by using his own miserable means – sooner or later he will induce rebellion. The power will finally waver from inside, at the moment when it tries to humiliate this silent opposition with brutal means.

Were we mistaken? In November 1989, the day when the group of Nadj and MAKUZ – the Hungarian Royal Court Orchestra, under the musical direction of Szabados – performed for the first time the dance opera in Brest (France), the Berlin Wall came down.

Translation by Marianne Tharan (October 2017)

Tanzoper: Tod des Gouverneurs

Auszüge aus den Notizen, die Gyula Kodolányi im Jahr 1997 über die Abläufe eines „Totalen Theaters“ geschrieben hat:

Gyula Kodolányi: NOTIZEN ZUM „TOD DES GOUVERNEURS”

Mein Gedichttext ist kein Libretto. Dieser Zyklus trägt in sich die Erwartungen im Jahr 1989, dieses vergehenden, glänzenden historischen Moments, parallel mit dem noch aktiven Erlebnis der Diktatur. Die Entstehungsgeschichte des totalen Theaterwerkes kann dem Leser den “Tod des Gouverneurs” näher bringen.

Die Idee des „Todes des Gouverneur“ begann sich in der Fantasie meines Freundes, des Komponisten György Szabados im Jahr 1986 zu formen und zu entfalten. Szabados wurde auf die in den Überlieferungen des ungarischen Volksschauspiels fragmentarisch auftauchenden, vergessenen mythischen Elemente aufmerksam und in diesen erkannte er die Verwandtschaft mit den Motiven des japanischen und chinesischen Theaters. Diese veranlassten ihn ein solches zeitgenössisches Spiel zu schaffen, worin die Betrachtungsweise und der Stil des Kabuki-Theaters durch unsere Probleme, durch unsere Empfindsamkeit durchschimmern.

Szabados dachte an ein Spiel, in dem Musik, Rezitation und Bewegung die gleiche Rolle einnehmen — und das ganz anders ist als alles, was wir als Oper oder Ballett kennen. In gewisser Hinsicht stilisierter, rauer. Nicht anekdotisch und nicht naturalistisch.

Szabados befreundete sich damals, bei einem Besuch in der Region Bácska mit József Nagy, alias Josef Nadj, dem Choreographen-Tänzer des Theaters Jel, der sich gerade für seine erste große Produktion vorbereitet hatte: „Die Peking Ente”. Dadurch wurde er zu einem der führenden Persönlichkeiten des modernen Tanztheaters in Paris. Als er „Die Peking Ente” und die Arbeit von Nadj sah, erkannte Szabados, dass das, was er in seiner Fantasie nur als Spiel gestaltet hatte, verwirklicht werden konnte, weil Regisseur und Theater da waren, die etwas Ähnliches machen wollten.

Ich schloss mich der Erarbeitung des Spiels im Frühling 1989 an. Szabados erwähnte mir gegenüber bereits 1988 diese Zusammenarbeit und dass er einen Texter suche, aber damals ergriff ich noch nicht die Gelegenheit. Ich hatte noch nie ein Bühnenstück geschrieben und meine Vorstellungen über Drama waren von anderer Art. Zur Zeit meiner beginnenden Mitwirkung bestimmten die Hauptzüge der Handlung und die Tonart des Werkes bereits den Bewegungsraum. Von nun an entstanden die drei Fäden: Tanz, Musik und Gedicht auf separaten Wegen, aber gleichzeitig und auf einander einwirkend. Nadj brachte die neuen Videoaufnahmen von den Proben in Paris mit. Wir haben diese mit ihm, mit den Musikern und wir zwei dann mit Szabados durchdiskutiert. Ich lieferte Szabados und Nadj die neuen Gedichte für unsere endlosen aber sehr sachgerechten Diskussionen in Nagymaros. Szabados bewertete die Arbeit von uns beiden, indem er uns die Dynamik der Musik und die Wellenbewegung des Dramas vor Augen hielt.

Da war kein fertiges Drama zum Vertonen und dann zum Choreographieren. Da war keine fertige Geschichte, die ein Libretto nötig hatte. Wir haben zusammen etwas geschaffen, Schritt für Schritt, mit Sprüngen und Abweichungen, im freien Raum der großen, imaginären Form: es war außerordentlich schwierig, aber auch befreiend.

Wir drei fügten dem „Tod des Gouverneurs” verschiedene Dimensionen hinzu. Szabados vertrat die Meinung, wie ich auch, dass die Bewegung eher, früher und tiefer wurzelt als Musik und Dichtkunst. Nadj stellte sich die Geschichte vor, die die Tanzbühne in der Sprache der Bewegung erzählen kann, und dazu war eine neue Musik nötig, die nebst ihrer Eigengesetzlichkeit dieses Bühnengeschehen volle Aufmerksamkeit widmete. Und im Stadium der Reifung musste sich der Tanz wieder den Wegweisern der sich entfaltenden Musik anpassen, die schon in meinem Text zum Rezitieren beinhaltet waren. Der bloße Text beeinflusste jedoch die Tonart, die Formen, den Umfang der Musik.

Durch meinen Text trat der Erzähler selbst ins Drama – es war Tamás Kobzos Kiss bei der Aufführung – weil sich der in den Gedichten ausgedrückte Aspekt im „Tod des Gouverneurs” selbst bewegt. Er identifiziert sich zu Beginn völlig mit den Lügen, die den Tyrannen umgeben, und diese Heuchelei wird durch Verdrehungen und Purzeln in der Tonart enthüllt. Diese Textironie bleibt dem Vortragenden verborgen und die falschen Metaphern und Fehler machen für das empfindliche Gehör die Selbstverherrlichung der jeweiligen Diktaturen so tröstlich lächerlich.

Im Laufe des Spiels wird der Erzähler mit der Wirklichkeit konfrontiert, und erlebt eine fast so kraftvolle Erleuchtung, wie der Narr. Deshalb kann er die Schlussworte der Geschichte aufsagen, und sogar eine Art Zukunftsvision aufleuchten lassen, die sich auf das Licht reimt, das die Hausheilige am Ende des Spiels aufzeigt.

Zum Schluss müssen wir von der Stille sprechen, vom Theater der Stille.

1989 hatten wir das Gefühl, dass nun die Zeit für die übertreibende Pantomime der Lüge und die extremen, sich in ihren Gegensatz verkehrenden Emotionen gekommen war. Der Gouverneur begießt die mit Gewalt zusammengezimmerte soziale öffentliche Verständigung mit der Soße der lügenhaften Selbstgefälligkeit: in dieser Welt herrschen also die ,,doppelte Sprache”, das Beinstellen und das geheime Spiel in jeder menschlichen Beziehung. Nur zwei – äußerlich tragikomische, innerlich jedoch umso stärkere menschliche Stimmen ertönen aus dem Chor der Heuchelei: die Liebe des Narren (und Hofdichters) zur Hausheiligen, und das Mitleid der Hausheiligen dem Gouverneur gegenüber. Es stellt sich heraus: wenn jemand in dieser Welt ohne eigenes Zutun gut oder „anders” sein will, – der „schön und frei und mild” mit seinen erbärmlichen Mitteln sein will – der verursacht früher oder später Skandal und Rebellion. Die Macht gerät innerlich endgültig dann ins Schwanken, wenn sie versucht, diesen stillen Widerstand brutal zu erniedrigen.

Haben wir uns geirrt? Im November 1989, an jenem Tag, als die Truppe von Nadj und MAKUZ – das Ungarische Königliche Hoforchester – unter der Leitung von Szabados in Brest in Frankreich die Uraufführung hatten, fiel die Berliner Mauer.

Produkció: a Quartz de Brest, Theatre de la Ville-Paris, L’hippodrome-Douai, Centre de Production Choregraphique-Orleans. Graceau concours de la Fondation Beaumarchais megbizásából az AlphaFnac részvételével

Koprodukció : Le Quartz Scene Nationale de Brest, Theatre dela Ville (Paris), L’Hippodrome (Douai) , Centre Choreographigue National d’Orleans

Előadó társulat : Jel Színház

Koreográfus és rendező : Nagy József

Tánc : Sárvári József (a Kormányzó) – Debrei Dénes (az Őrült) – Maire Helene Mortureux (a kis szent) – Szakonyi György (az Orvos) – Hudi László (a Varázsló) – Kathleen Reynolds, Cecile Thieblemont (a Nők) – Nagy József, Frederic Lescure (a szolgák, a filozófusok).

Díszlettervező : Goury

Jelmezek : Catherine Rigault

Maszkok : Jean-Marie Binoche

Világítás : Remi Nicolas, asszisztense : Sylvie Vautrin

Versek: Kodolányi Gyula

A magyar zeneszerző, Szabados György eredeti zenéjével, amelyet a színpadon a budapesti MAKUZ Együttes tizenegy zenésze adott elő

Zene: Szabados György a MAKUZ Együttessel

“Kobzos” Kiss Tamás (ének), Grencsó István (fúvósok), Dresch Mihály (fúvósok), Vaskó Zsolt (fúvósok), Kovács Ferenc (trombita), Mákó Miklós (trombita), Benkő Róbert (bőgő), Lőrinczky Attila (bőgő), Geröly Tamás (ütőhangszerek), Baló István (ütőhangszerek), Szabados Gyorgy (zongora).

Hangmérnök: Pierre Jacquot

Production: Commissioned by the Quartz de Brest, Theatre de la Ville-Paris, L’hippodrome-Douai, Centre de Production Choregraphique-Orleans. Graceau concours de la Fondation Beaumarchais, with the participation of AlphaFnac.

Coproduction: Le Quartz Scene Nationale de Brest, Theatre dela Ville (Paris), L’Hippodrome (Douai) , Centre Choreographigue National d’Orleans

Company: Theatre Jel

Choreography and stage setting: Josef Nadj

Dance: Joszef Sarvari (the Governor) – Denes Debrei (the Madman) – Marie-HeldneMortureux (the little Saint) – Gyork Szakonyi (the Doctor) – Laszlo Hudi (the Magician) – Kathleen Reynolds, Cecile Thidblemont (the Women) – Josef Nadj, Freddric Lescure (the Servants, the Philosophers).

Stage design/Scenography: Goury

Costumes: Catherine Rigault

Masks: Jean-Marie Binoche

Lighting Design: Remi Nicolas assisted by Sylvie Vautrin

Poet: Gyula Kodolanyi – book

Original Music by the Hungarian composer: György Szabados, interpreted on stage by the eleven musicians of the ensemble Makuz of Budapest.

Music: György Szabados with MAKUZ Orchestra

Tamás Kiss “Kobzos” (vocals), Grencsó István (sax, flute,clarinet), Dresch Mihály (sax, flute, bass clarinet), Vaskó Zsolt (flute, piccolo), Kovács Ferenc (trumpet), Mákó Miklós (trumpet), Benkő Róbert (bass), Lőrinczky Attila (bass), Geröly Tamás (percussion), Baló István (percussion), Szabados Gyorgy (piano).

Sound Direction: Pierre Jacquot

Note:

![]() Information where and when the composition was performed

Information where and when the composition was performed

![]() Programm info

Programm info

![]() Mikroorganizmusok [In: Magyar Szó, 1989, 7 April, page 11]

Mikroorganizmusok [In: Magyar Szó, 1989, 7 April, page 11]

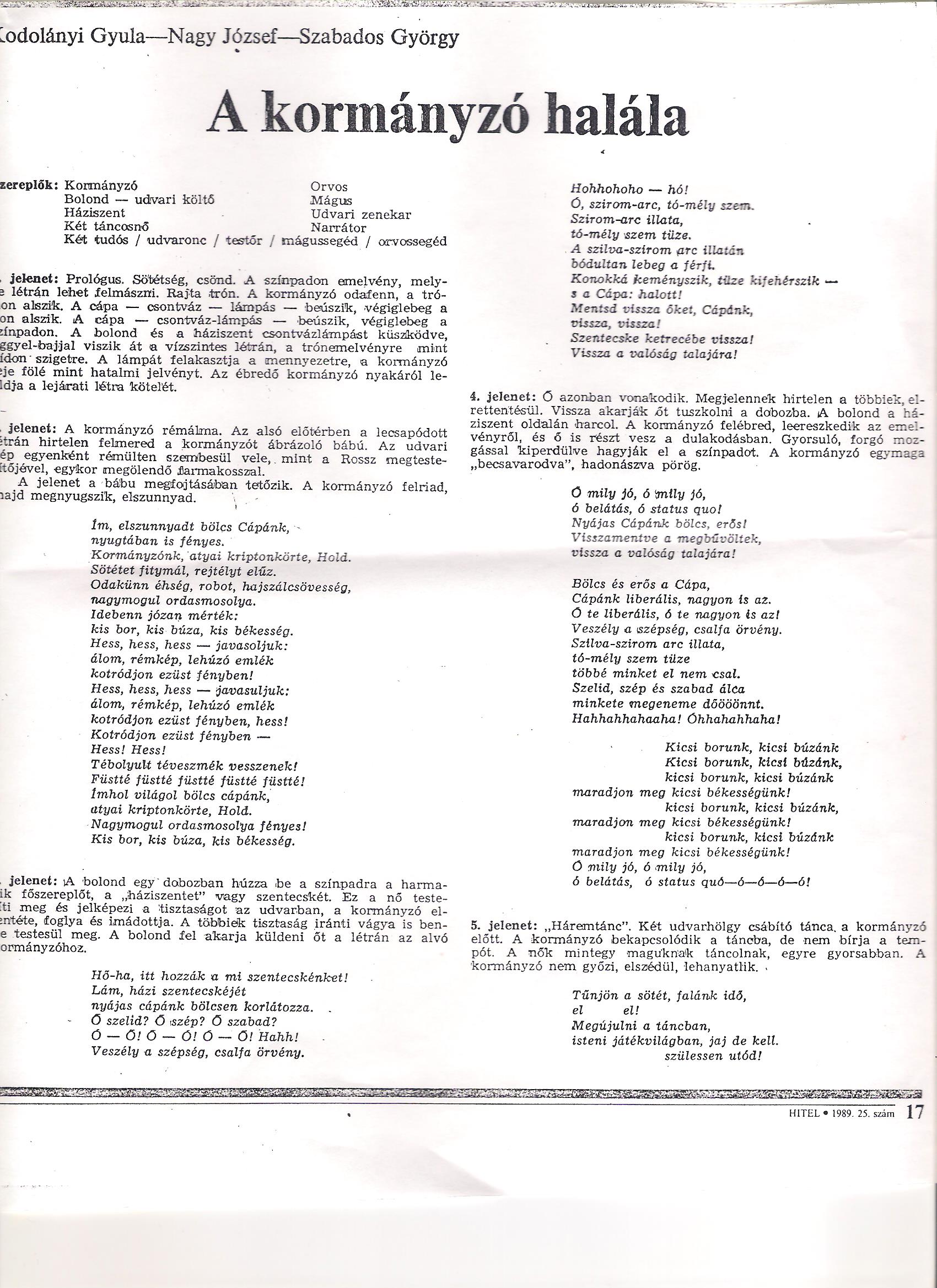

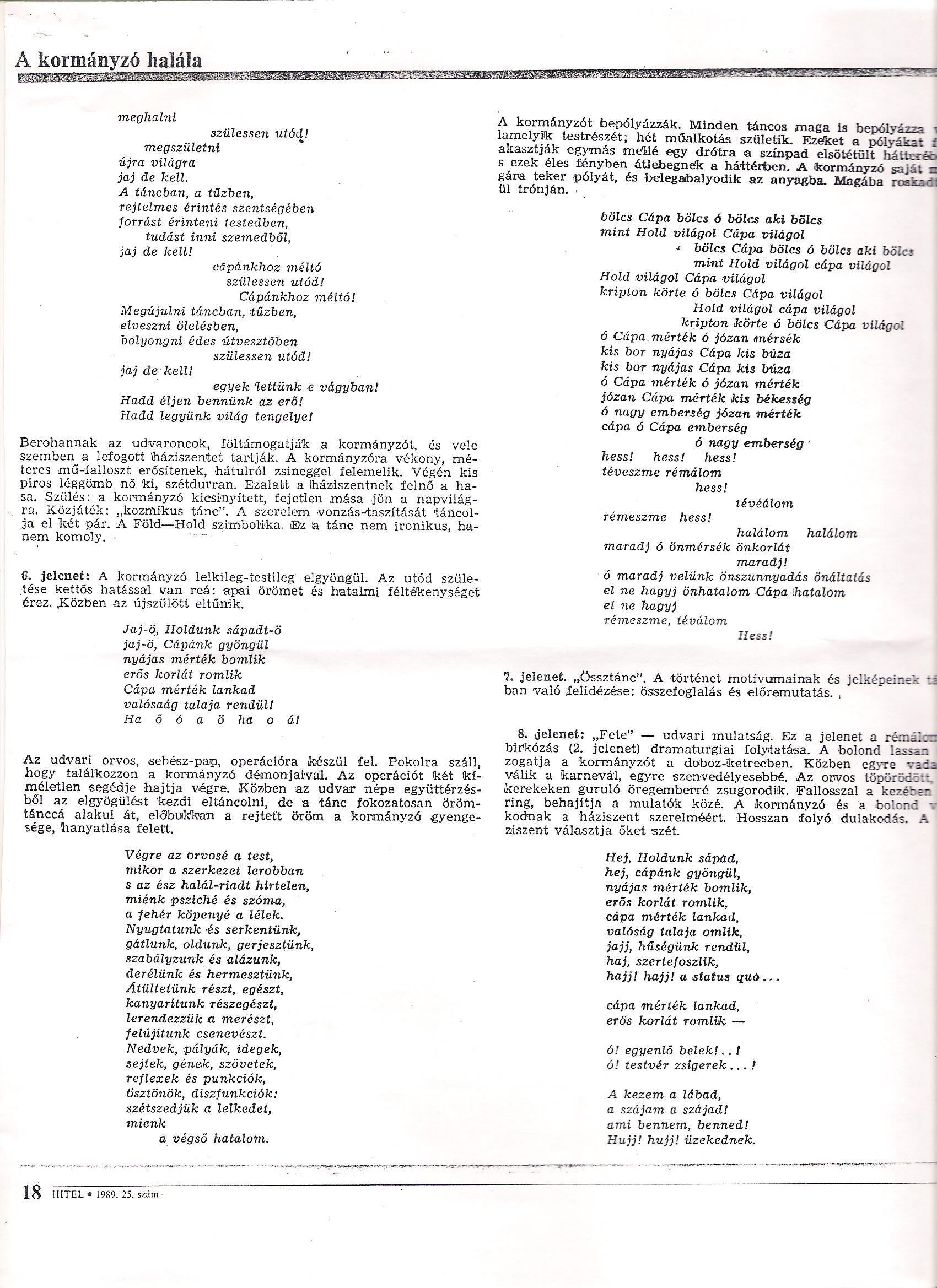

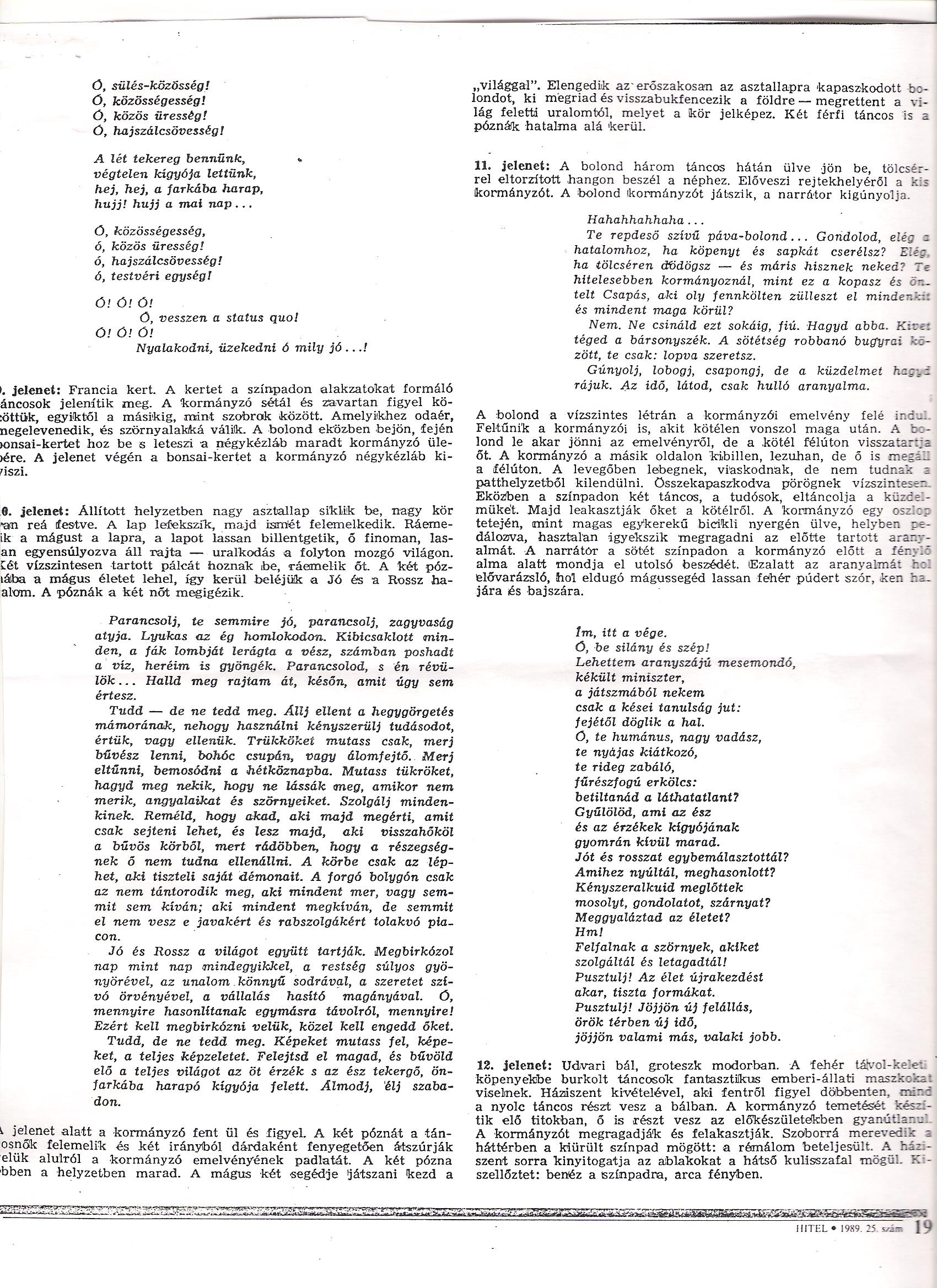

![]() Text of the opera by Gyula Kodolányi [In: Hitel, 1989, special issue, page 17-19]

Text of the opera by Gyula Kodolányi [In: Hitel, 1989, special issue, page 17-19]

![]() Gyula Kodolányi’s essay about the creation of the opera [In Hitel 1990 No. 3, page 29-33]

Gyula Kodolányi’s essay about the creation of the opera [In Hitel 1990 No. 3, page 29-33]

![]() Klaus Witzelin: Ein Glanzlicht zum Festival-Abschluss [In: Hamburger Morgenpost 1990, 6 Aug.]

Klaus Witzelin: Ein Glanzlicht zum Festival-Abschluss [In: Hamburger Morgenpost 1990, 6 Aug.]

![]() Conversation on The Governor’s Death with György Szabados and Gyula Kodolányi in the TV2, Budapest (HU)

Conversation on The Governor’s Death with György Szabados and Gyula Kodolányi in the TV2, Budapest (HU)

![]() Interview by Tóth Ádám with György Szabados: A “megtorpedózott” kormányzó [In: Pesti Műsor, 1992, 15 May, page 2]

Interview by Tóth Ádám with György Szabados: A “megtorpedózott” kormányzó [In: Pesti Műsor, 1992, 15 May, page 2]

![]() Kodolányi Gyula – A létezés-szakmában (KÉRDEZ: LIPTAY KATALIN) [In: Kortárs, 1998/8, page 53-55]

Kodolányi Gyula – A létezés-szakmában (KÉRDEZ: LIPTAY KATALIN) [In: Kortárs, 1998/8, page 53-55]

![]() Comments in the subject of The Governor’s Death (A Kormányzó halála) [In: György Szabados – Writings I., 2008, page 187-207]

Comments in the subject of The Governor’s Death (A Kormányzó halála) [In: György Szabados – Writings I., 2008, page 187-207]

![]() Gyula Kodolányi

Gyula Kodolányi

![]() Josef Nadj

Josef Nadj

![]() Pictures

Pictures

PLAYLIST:

read more infos about playlist: #1: 4:28 Musicians: Related items: #2: 89:15 Musicians: Related items: #3: 47:39 Musicians: Related items: #4: 79:57 Musicians: Related items: #5: 34:21 Musicians:

Recording Date: 9, November 1989

Recorded at: unknown place, Brest (FR)

Szabados Gyorgy (composer, piano, conductor)

Tamás Kiss “Kobzos” (vocals)

Grencsó István (sax, flute,clarinet)

Dresch Mihály (sax, flute, bass clarinet)

Vaskó Zsolt (flute, piccolo)

Kovács Ferenc (trumpet)

Mákó Miklós (trumpet)

Benkő Róbert (bass)

Lőrinczky Attila (bass)

Geröly Tamás (percussion)

Baló István (percussion)

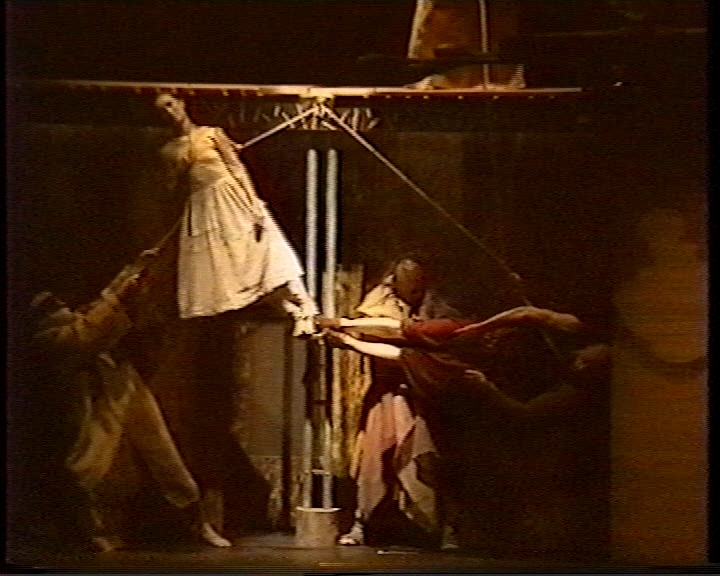

![]() Video of the perfromances (excerpt)

Video of the perfromances (excerpt)

———————

Recording Date: 6. December 1989

Recorded at: JEL Theatre, Orleans (F)

Szabados Gyorgy (composer, leader, piano)

Tamás Kiss “Kobzos” (vocals)

Grencsó István (sax, flute,clarinet)

Dresch Mihály (sax, flute, bass clarinet)

Vaskó Zsolt (flute, piccolo)

Kovács Ferenc (trumpet)

Mákó Miklós (trumpet)

Benkő Róbert (bass)

Lőrinczky Attila (bass)

Geröly Tamás (percussion)

Baló István (percussion)

![]() Video recording

Video recording

———————-

Recording Date: unknown day, June 1990

Recorded at: unknown place in Lievin (F)

Szabados György (composer, conductor, piano)

„Kobzos” Kiss Tamás (vocal-recital)

Baló István (percussion)

Benkő Róbert (cello)

Dresch Mihály (reeds)

Geröly Tamás (percussion)

Grencsó István (reeds)

Kovács Ferenc (trumpet, violin)

Lőrinszky Attila (double bass)

Mákó Miklós (trumpet, tuba)

Vaskó Zsolt (reeds, jew’s harp)

![]() Video recording

Video recording

———————-

Recording Date: between 12 – 16. June 1990

Recorded at: Theatre de la Ville in Paris (F)

Szabados György (composer, conductor, piano)

„Kobzos” Kiss Tamás (vocal-recital)

Baló István (percussion)

Benkő Róbert (cello)

Dresch Mihály (reeds)

Geröly Tamás (percussion)

Grencsó István (reeds)

Kovács Ferenc (trumpet, violin)

Lőrinszky Attila (double bass)

Mákó Miklós (trumpet, tuba)

Vaskó Zsolt (reeds, jew’s harp)

![]()

![]() Audience recording

Audience recording

———————-

Recording Date: November, 16, 1991

Recorded at: Vigadó Music Hall, Budapest (HU)

Szabados György (composer, conductor, piano)

„Kobzos” Kiss Tamás (vocal-recital)

Dresch Mihály (reeds)

Grencsó István (reeds)

Mákó Miklós (trumpet, tuba)

Kovács Ferenc (trumpet, violin)

Benkő Róbert (double bass, cello)

Geröly Tamás (drums, percussion)

VIDEOS:

November, 9, 1989, at unknown location in Brest (F):

Time total: 4:28 (excerpt)

György Szabados with “MAKUZ”:

Szabados Gyorgy (composer, piano, conductor)

Tamás Kiss “Kobzos” (vocals)

Grencsó István (sax, flute,clarinet)

Dresch Mihály (sax, flute, bass clarinet)

Vaskó Zsolt (flute, piccolo)

Kovács Ferenc (trumpet)

Mákó Miklós (trumpet)

Benkő Róbert (bass)

Lőrinczky Attila (bass)

Geröly Tamás (percussion)

Baló István (percussion)

6. December, 1989, at JEL Theatre, Orleans (F):

Time total: 89:15

György Szabados with “MAKUZ”:

Szabados György & MAKUZ:

Szabados Gyorgy (composer, leader, piano)

Tamás Kiss “Kobzos” (vocals)

Grencsó István (sax, flute,clarinet)

Dresch Mihály (sax, flute, bass clarinet)

Vaskó Zsolt (flute, piccolo)

Kovács Ferenc (trumpet)

Mákó Miklós (trumpet)

Benkő Róbert (bass)

Lőrinczky Attila (bass)

Geröly Tamás (percussion)

Baló István (percussion)

June, unknown day, 1990, at unknown location, in Lievin (F):

Time total: 47:39

György Szabados with “MAKUZ”:

Szabados Gyorgy (composer, piano, conductor)

Tamás Kiss “Kobzos” (vocals)

Grencsó István (sax, flute,clarinet)

Dresch Mihály (sax, flute, bass clarinet)

Vaskó Zsolt (flute, piccolo)

Kovács Ferenc (trumpet)

Mákó Miklós (trumpet)

Tréfás István (violin)

Benkő Róbert (bass)

Lőrinczky Attila (bass)

Geröly Tamás (percussion)

Baló István (percussion)

June, between 12 – 16 June, 1990, at Theatre de la Ville in Paris (F)

Time total: 3:52

Musicians:

Szabados György (composer, conductor, piano)

„Kobzos” Kiss Tamás (vocal-recital)

Baló István (percussion)

Benkő Róbert (cello)

Dresch Mihály (reeds)

Geröly Tamás (percussion)

Grencsó István (reeds)

Kovács Ferenc (trumpet, violin)

Lőrinszky Attila (double bass)

Mákó Miklós (trumpet, tuba)

Vaskó Zsolt (reeds, jew’s harp)

Conversation on Governor’s Death, 1990 – December 31, 1990. TV2, Budapest, Hungary

with excerpt from performance at:

June, between 12 – 16 June, 1990, at Theatre de la Ville in Paris (F)

Time total: 14:33

Contributors:

Szabados György

![]() Kodolányi Gyula

Kodolányi Gyula

Musicians:

Szabados György (composer, conductor, piano)

„Kobzos” Kiss Tamás (vocal-recital)

Baló István (percussion)

Benkő Róbert (cello)

Dresch Mihály (reeds)

Geröly Tamás (percussion)

Grencsó István (reeds)

Kovács Ferenc (trumpet, violin)

Lőrinszky Attila (double bass)

Mákó Miklós (trumpet, tuba)

Vaskó Zsolt (reeds, jew’s harp)

A mű szövege (Text of the work):

SHEET MUSIC:

Corrections and additions are welcome – please contact webmaster: info@györgy-szabados.com